Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 9:00:00 GMT -8

There’s a good epilogue in the book. More of this probably should have been integrated in the story. It’s interesting to learn that eventually, when all the hoops had been successfully jumped through regarding demonstrations and contract obligations, Wilbur and Orville did eventually fly together. They had avoided that until then for obvious reasons. Sister Katherine had now been aloft many times. But there was still one other:

|

|

|

|

Post by timothylane on Jan 20, 2020 9:04:36 GMT -8

As I mentioned earlier, the Smithsonian eventually did receive a Wright flyer to display. I don't know how they handled the issue of whether Langley or Wright deserved credit, but certainly every else credit goes to the Wrights. Most people have never heard of Langley, though the US Navy named its first aircraft carrier after him. (By the time we got into World War II it was no longer listed as a carrier. I think the Japanese sank it in the aftermath of the invasion of Java.)

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 9:10:23 GMT -8

Regarding the sudden appearance of so many flyers, the New York Times of the time said something interesting:

Kings, prime ministers, presidents, monarchs, dignitaries and movie stars were all drawn to the yuge spectacle of the flights of the Wright brothers in Europe, particularly France. In fact, the best part of the book is the description of the Wilbur (and later Orville and Katherine) in Paris. It’s worth a read.

At one point, King Edward VII, on holiday in France, came to see a demonstration of flying. He was apparently an interesting and interested fellow. The Wrights lived for a time in the lap of luxury and privilege but were notably not changed by it. But they did witness some interesting people. One passage in the book regarding the aristocracy is humorous:

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 9:22:32 GMT -8

Whether McCullough cherry-picked his information or not, it’s interesting to note that it seems most of the people were thrilled (in a good way) to take a ride in the air with one of the Wright brothers. You’d think they’d be scared out of their wits. I mean, you’re in an open aircraft, it’s a highly experimental aircraft, the wind is in your face, the noise of the engine behind is deafening, you’re moving at a speed you’ve probably never gone before (except within the safe confines of a train), and there is little between you and the ground.

And yet I think Wilbur’s description of flight is likely what most people felt, whether they were piloting or the passenger:

I went aloft in a small airplane only once. I was a small boy and don’t remember much. But I don’t think I was afraid and it was indeed rather thrilling. More than anything, at least for me, it was disorienting. Unlike the Wright brothers who mostly flew a hundred feet or so (where you could still, as some noted, recognize the faces of the people below), at several thousand feet, the world suddenly makes no sense. It’s something different. And my ride was so relatively short, I didn’t have the time to make much sense of what I was seeing.

And I’ve been in a jumbo jet. And there was the sense of being on a bus packed in with other people. Yes, there is somewhat a thrill because you do go up in the air. And that is pretty spectacular. But I suspect that the kind of ride that passengers took in a Wright brothers plane was a level above all that. What most seemed to comment on as well was had smooth the ride was, even while making turns.

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 10:14:40 GMT -8

One of the things that surprised me was to read that the magazine, Scientific American, has apparently always been arrogant and a bit corrupt.

One of the central characteristics (not themes…actually having opinions when writing these days seems verboten) of this book is how the United States government, the American press, and to a large extent Americans themselves dismissed what the Wright brothers were doing.

As I had said, early attempts at flight did tend to resemble patent medicine, the realm of cranks. And there were plenty of screwballs and cranks, harmless or otherwise. One can understand a general skepticism toward yet another claim of flying.

That said, the American press was arrogant and negligent and the flying was there for anyone to witness, as many did. It was up to a man (Root) who made his fortune selling beehive equipment and supplies to first publicize their achievements at Huffman Prairie where Root said:

But no one seems to care. Dayton’s own newspaper, the Dayton Daily News, took no notice:

But aside from the United States government, perhaps Scientific American was the worst:

Today, Scientific American is an obnoxious politically correct rag that spends as much time on pseudoscience as it does real discovery. But it did surprise me that their arrogance, if not innate corruptness, went back so far.

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 10:28:12 GMT -8

The Wright brothers were never mega-rich. But Orville was worth about a million dollars at the time of his death. This is a short book, and I can’t damn it for that. Far too many books could use a good editor. But I would have loved to learn a bit more about how they coped with the newly-made wealth. For one thing, in 1914 they moved from 7 Hawthorne Street to “the newly completed, white-brick, pillared mansion in Oakwood, which they had proudly named Hawthorn Hill.  Baby. That’s one cool mansion. For all the humility and good character maintained by the Wright family, they did splurge a bit. They were not quite Quakers.

Other uses of their money:

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 10:39:16 GMT -8

Here’s some more info about the island: More info: One gets the obvious impression from the McCullough book that the Wright family lived a rich and adventurous life. To the Europeans (the French, in particular), they were the embodiment of the American ideal: no-nonsense men who worked hard and achieved something. The French wildly embraced them (including Katharine) with open arms. The affection was genuine in both directions, as difficult as celebrity could be for them at times. But they bore these burdens with grace. That is, they were not Megyn and Harry. |

|

|

|

Post by timothylane on Jan 20, 2020 10:39:41 GMT -8

As far as I know, I've never been in a small plane. The first flight I can remember being on was our flight from Rome to Athens in 1961 (we went by Army transport from New York to Naples and then by car to Rome). The next was our flight from Athens to Madrid in 1964, followed (after a few days sight-seeing) by a flight from Madrid via Lisbon (we were there for so little time we didn't get off the plane) to New York. I'm not sure when the third flight was (it may have been Louisville via St. Louis to Minneapolis in 1974). Of course these were all on jet airliners. The only time I remember being on a non-jet was on a commuter flight from Indianapolis to Fort Wayne.

It's unsurprising that few people took the Wright brothers seriously before they made their flights. No doubt everyone expected a major project such as Langley's to be the route to success. Never mind how many major inventions came from ordinary people working in their shops. (Hello, Mr. Bell. This is Mr. Morse. We have Mr. Howe, Mr. Singer, and Mr. McCormick over here. Mr. Tesla is expected shortly, and Mr. Edison already left rather than meet him.) Perhaps it was because Edison had been so successful that he had set up his own large outfit at Menlo Park by then.

But it's surprising that there was so much skepticism about aviation even after they succeeded. Granted, their invention wasn't very practical yet, but it quickly developed once people knew what they needed to do.

Incidentally, my daily list of Kindle books today includes McCullough's book on the Wright brothers. I'm currently reading something else, but that will probably be my next read.

|

|

|

|

Post by timothylane on Jan 20, 2020 10:47:15 GMT -8

Impressive mansion. Note that a million dollars before World War I was a heck of a lot, though probably not at the Trump level. A century of overall inflation has taken a heavy toll. (An interesting trick is known as the Rule of 72. If you divide the rate of inflation into 72, you get how many years it takes to halve the dollar's value. I first read about this in F. Paul Wilson's An Enemy of the State, and a friend with a BS in physics and a BA in math says it has to do with the square root of 2.)

Incidentally, James Cox was the Democrat presidential nominee in 1920, losing very badly to fellow Buckeye Warren G. Harding. (His VP nominee, Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York, didn't lost heart despite being so badly defeated.) I assume it was the same guy.

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 11:03:48 GMT -8

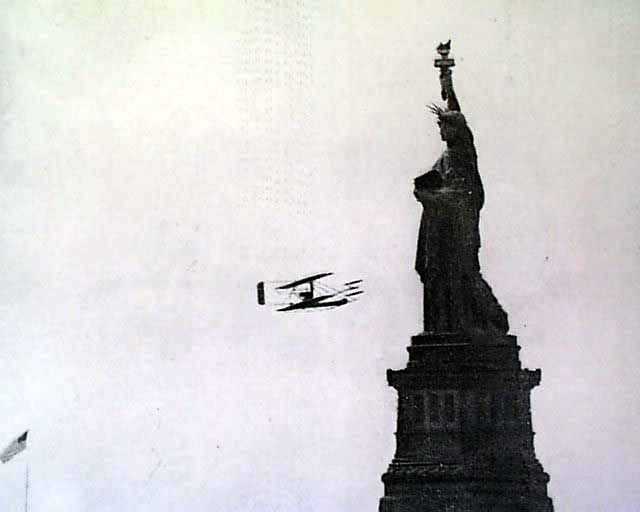

That is the conceit of “official channels,” Big Government, and Deep Pockets. The Langley group spent $70,000 on a complete failure (one that was such an embarrassing failure, they resorted to fraud to try to clear their reputations). The Wright brothers spent$1,000. Certainly there were harsh skeptics in France. The general impression was that the Wrights had been secretive and therefore had something to hide — particularly that their achievements were not what they (or some people) said they were. The proof was in the pudding. Upon making one successful flight at Le Mans, even their harshest and most noxious skeptics were groveling at their feet and admitting that they were wrong. The French may be faulted for many things. But not about the early adoption of, and innovation in, flying. But the Americans…yikes. They just didn’t want to believe. Even with the early and clear evidence at Huffman Prairie, most dismissed it. They didn’t believe the eye witnesses. One gets the distinct impression that Alexander Graham Bell was an asshole. In fact, the first air casualty (Thomas Selfridge) was considered a plant by the Wright brothers. Later, Bell all but broke into the shed to steal information about the Wright’s aircraft. It’s astounding in our own time to read how New York City came to almost a standstill when Wilbur (and another…who later had to beg out) were on Governors Island and it was known that they were going to do a flyby of the city. The photo of Wilbur circling the Statue of Liberty is a truly iconic moment.  Wilbur, being of a cautious mind, strapped a canoe underneath in case he had to land in the water. Today, of course, jumbo jets pass overhead and we barely take notice. But there was a time when a single and simple aircraft was as scene-grabbing as if aliens had just landed on the Washington Mall.  |

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 11:50:31 GMT -8

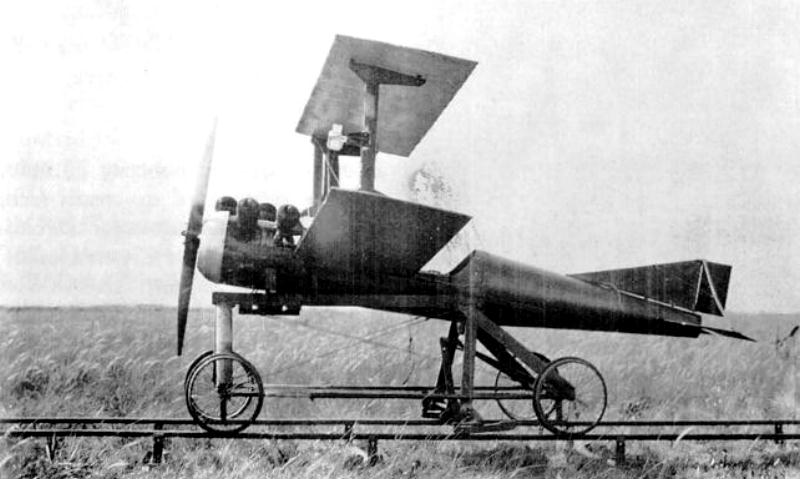

I’m going to give you enough impression heres, you’re not going to need to read the book. One of those impressions was how unlike, say, Edison, the Wright brothers didn’t build a mega empire. This source says: I’m the world’s worst entrepreneur. And from what I can see, the Wright brothers were very good in business. Still. it seems they were a “spectacle” the way they went about things and less of an enterprise. The thought in my head while reading this is that they should have sub-contracted out to the mega-factory in Dayton (The Davis Sewing Machine Company had a factory “fully a mile in length”) to start building the planes. They should have had sales receipts in hand after each demonstration and ready to take orders. $5,000 a pop. But there was nothing wrong with their strategy to get government orders, which they did. But its clear the industry quickly advanced beyond them. And the Wright brothers become worthy figureheads of the invention of flying. But Boeing they were not. This is somewhat informed speculation on my part. Again, it seems to be the thing these days in non-fiction books not to have an opinion or offer much in the way of substantive analysis. The facts (more or less…and the facts you present can certainly substitute for an opinion) are included and the reader is left to read between the lines. I don’t mind reading between the lines. But those (such as McCullough) who have just been immersed in this research are in a better position to do so. The Wrights did produce various models of airplanes which you can see here. If they had an impact on aviation beyond kick-starting it, this book gives no clue. And that seems to be an omission. By 1915 the Wright Company was producing the Model K which was their first to use ailerons (something they had mentioned in their initial patent but the book is unclear as to whether they had actually patented the concept or not). As already noted, back in 1909 (and you can measure those single years as “dog years” in the early days of aviation), the airplane that Blériot designed to cross the English Channel used ailerons. I’m not saying that the Wrights weren't successful and innovative later on. But none of the planes that I see on the page stand out as household words. And in their own words, they say it is a shame they had to spend so much time protecting their patents instead of being able to innovate. Finally in the 1916 Model L, they did away with the chain drive and had a plane with a single propeller mounted directly to the engine. It would seem to took the years to catch up to what others had been doing in 1909. There was an interesting aircraft in the 1918 Liberty Eagle:  That is a concept quite ahead of its time. |

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 11:55:59 GMT -8

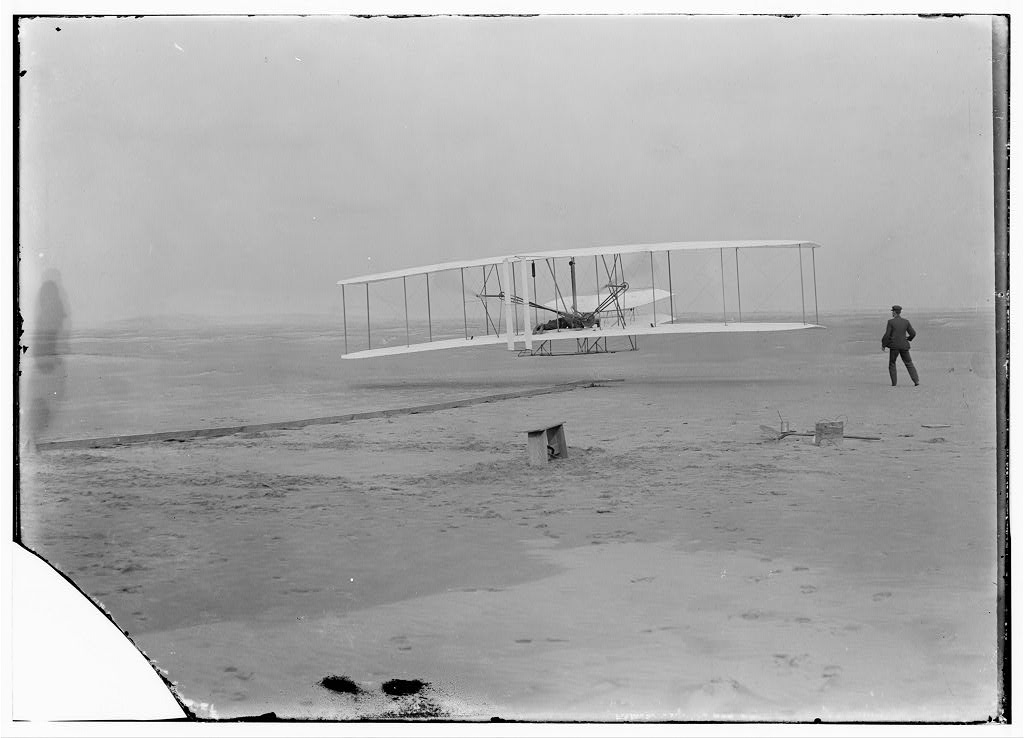

I found this very interesting photo (this is the iconic photo) of the first flight. It's interesting because it seems to be a contact print from the glass plate — at the time or perhaps it still exists.  [ Original] |

|

|

|

Post by kungfuzu on Jan 20, 2020 13:15:46 GMT -8

I believe there is a film of one of the flights which the Wright brothers made in France.

|

|

|

|

Post by kungfuzu on Jan 20, 2020 13:19:11 GMT -8

To give an example of what someone might do in the early years of flight, Glenn Curtis, against whom the Wrights fought legal battles, walked away with over US$30 million in the 1920s or 1930s, when he sold his shares of the company he founded.

The Wrights are symbolic of why most successful businessmen say, "Let somebody else pave the way, and I'll drive down it."

I have always had a soft spot for Bleriot as he had the good taste to make his first English Channel flight on my birthday, albiet some 44 years prior to my arrival.

|

|

|

|

Post by kungfuzu on Jan 20, 2020 14:05:26 GMT -8

Here is a short video with various shots of the Wrights flying their planes.

|

|

|

|

Post by artraveler on Jan 20, 2020 14:44:46 GMT -8

The Air Museum at McClellen air park, formerly AFB, has a pilots license signed by Orvial Wright, dated sometime in the 30s.

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 15:45:25 GMT -8

Yes, Curtiss was the corporate pirate that the Wright brothers had problems with. They won all of their patents disputes but may have lost the war. Still, I can appreciate that the Wright brother were operating under a different paradigm. They were craftsman who wanted to do good work. But, again, the lack of analysis or perspective in this book is telling. They were very much the technological equivalent of “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.” And yet it stuck very deeply in their craw that anyone would pilfer their work. And that’s fine. It appears it wasn’t the money they were trying to protect but their credit for inventing the first workable airplane. And then I sort of get confused because of all the blank holes in this story. On the one hand, they seemed egalitarian in the way they were freely demonstrating their airplane. Both logged hundreds of flights. Some of these flight were to meet contract obligations. But most seemed to be just for the love of flying. They charge no admission fees to see them.

And whose head isn’t turned when you have tens of thousands of people waiting for hours in the stands while the brothers waited for the wind to be just right? And sometimes it wasn’t right and all and they’d have to call it off and the crowds would have to come back tomorrow….and they usually did. I find it difficult to characterize what they were doing with their early demonstrations. They certainly didn’t seem to have an eye to maximizing their return. But neither did they want to simply give it away. Frankly, I think they were having way too good of a time in Paris to really give a damn. They were having the time of their lives. And when they left Europe in 1909 (or thereabouts), Europe was at peace and sort of like a very large Disneyland for the jet-setting crowd (although there were no jets yet). And subsequent events made them realize that they would never be able to return to that same Europe. How sad what a mess it became. Even now, many parts are dangerous because of the induced Muslim invasion. Here’s three entries from a timeline that I think show some missed opportunities for the Wright brothers. While they were concentrating on military contracts, there was a lot they missed: — Summer 1909 — The Wrights' sale of the first military flying machine is overshadowed by news from France. Louis Bleriot, flying a small monoplane of his own design, has crossed the English Channel. Although it is a relatively short flight, Bleriot has conquered an important physical and national boundary. Suddenly, people begin to realize the importance of this new invention. Summer 1909 — Glenn Curtiss joins with Augustus Herring to create an airplane manufacturing company, and sells his first aircraft — the Golden Flyer — to the Aeronautical Society of Long Island, New York. The Wrights file a suit against Curtiss and other airplane manufacturers who are infringing on their patent. Summer 1909 — Glenn Curtiss is the only American entry at the Reims Air Meet in France — the first international gathering of aviators and airplanes. He captures the Gordon Bennett Trophy for the fastest airplane and is an instant hero on both sides of the Atlantic. His fame raises his reputation as an aircraft builder to an even par with the Wrights. Fall 1909 — Both Curtiss and the Wrights are invited to fly for the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York, New York. Unable to fly his underpowered aircraft in the heavy winds, Curtiss defaults. Wilbur Wright shows him up, flying around the Statue of Liberty then up the Hudson River to Grant's Tomb and back. Over a million Americans see him fly. — It would have been trivial for the Wright brothers to fly over the English Channel. It was a 20 minute ride, at best, and at one point they were in the air for an hour or more. Granted, they couldn’t be everywhere. But they for a moment had the monopoly on it. While they were basically thrilling the crowds in a de facto traveling aerial circus at various places in France, Italy, and Germany, others were busy and thinking longer term. One thing I read about that is that they didn't want to showboat. But what could one call all those countless demonstrations? Wilbur eventually gains some measure of revenge when Curtiss backs out of the Governor Island show. The book said he had other commitments and could not hang around for the wind to become favorable. Wilbur decided to risk it and took off before the winds got worse. There was nothing said in the book about Curtiss’ plane being underpowered. Who knows? I think from day one the Wrights needed a way to sell, or license for manufacture, their planes to all comers. And they needed to hire some good lawyers and just let them do their job. Again, there is no background or perspective regarding the details. But in 1929 it became a moot point when the two companies merged to form Curtiss-Wright Corporation…a fact the book did not mention. That seems like a bit plot point worth mentioning. And the legend lives on: Curtiss-Wright CorporatioinA factoid there notes that “Curtiss-Wright is one of the leading manufacturers of ‘black box’ data recorders used on aircraft world-wide.” They needed one in Myer Field, although Orville immediately guessed what had happened: A broken propeller blade caused excessive vibration which worked a cable loose which then wound around the propeller blade and (by warping the wing, I suppose) caused the plane to dive into the ground. They fell from something like 75 feet. Orville was lucky to be alive. His dutiful sister (way above and beyond the call of duty) likely saved his life through her TLC. |

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 16:06:00 GMT -8

It must have been an amazing thing being up in one of the first airplanes. And then to have done something like being the first to cross the English Channel. The first person to swim the English Channel was Matthew Webb in 1875. The fastest was by an Australian, Trent Grimsey, who in 2012 did it in 6 hours and 55 minutes. The most crossings (43) is by Alison Streeter. The first attempt at jumping the English Channel was some time around 1970. |

|

|

|

Post by timothylane on Jan 20, 2020 16:12:20 GMT -8

It's unfortunate that many inventors have been poor businessmen. Edison was very unusual that way. The Wrights weren't as bad as some, perhaps because of their experience running a bicycle shop. But evidently they had a small business mindset.

Incidentally, the Wrights (I don't remember specifically which one took part) were involved in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, about an air race from Britain (perhaps London) to Paris. It would presumably have been some time between 1909 and 1914.

|

|

Brad Nelson

Administrator

עַבְדְּךָ֔ אֶת־ הַתְּשׁוּעָ֥ה הַגְּדֹלָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את

Posts: 12,272

|

Post by Brad Nelson on Jan 20, 2020 16:22:01 GMT -8

Their father had told them that all they needed was to make enough money so that they weren’t dependent upon other people. They did that in spades. Wilbur was the Rock of Gibraltar when he traveled to Europe with his would-be business partners. Wilbur resisted giving away the store. But, again, the business dealings as written up on the book are a bit vague. In the end, they made more money than they needed. Both brothers were extremely mechanical-minded. They could build just about anything…except the engines which they left to Charles Taylor. He’s sort of “the fifth Beatle.” He was absolutely central to the endeavor. The book doesn’t mention how he made out financially. Taylor apparently hand-build the engine, using an aluminum block. Whether he cast the engine himself, or it was an off-the-shelf part from some other engine, the book is silent on the matter. This website has a little more info on the engine, although it says “the brothers designed and built a gasoline powered internal combustion engine..” But it seemed very clear in the book that neither brother did engines. It was completely in the hands of Charles Taylor. |

|